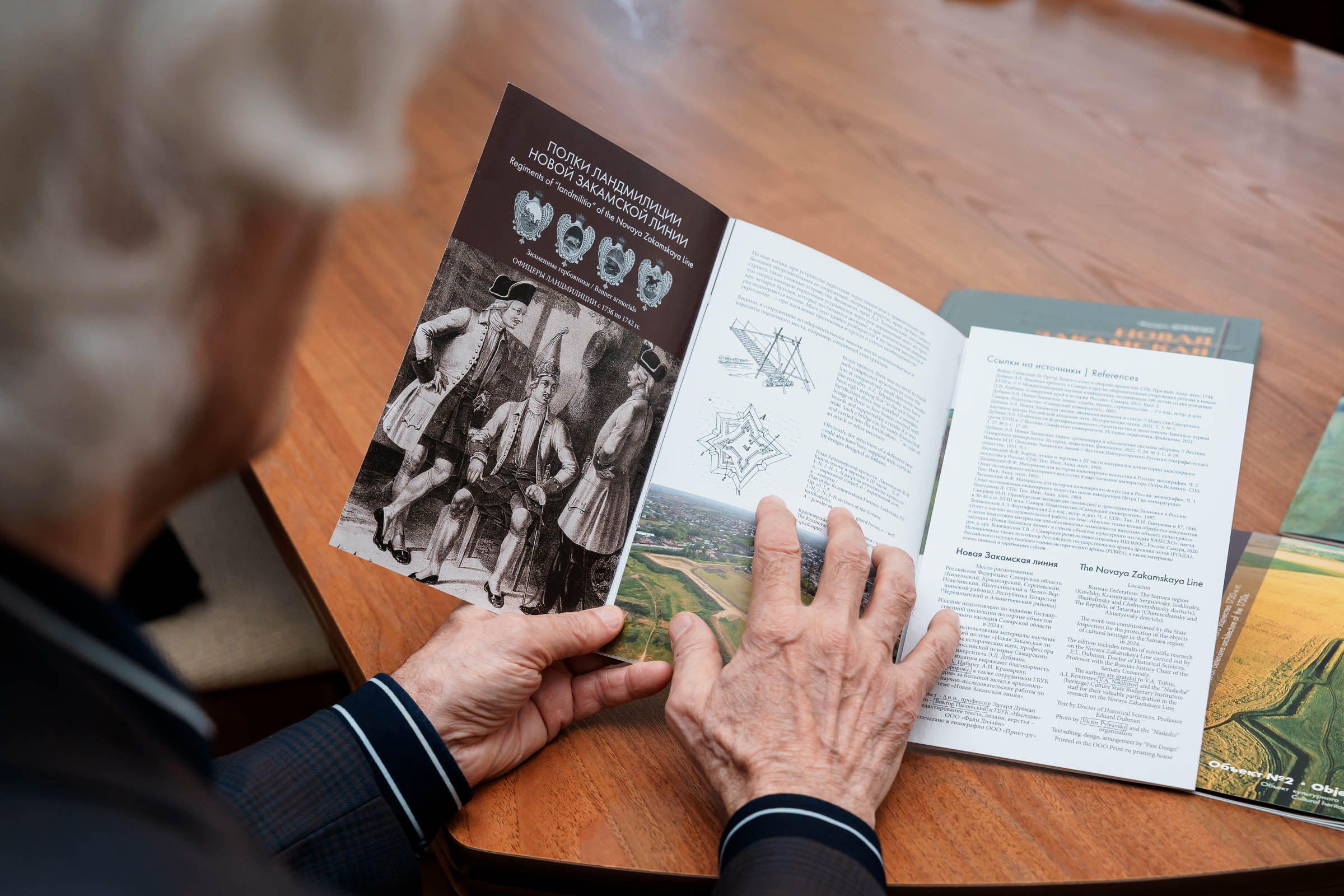

The first popular scientific guide to one of the largest defensive systems in Russia of the 18th century has been published in Samara. It is known as the New Zakamskaya Line. This historical landmark of the southern forest-steppe Trans-Volga region, which is a system of fortifications with a total length of about 260 km, is located in the Samara region and the Republic of Tatarstan.

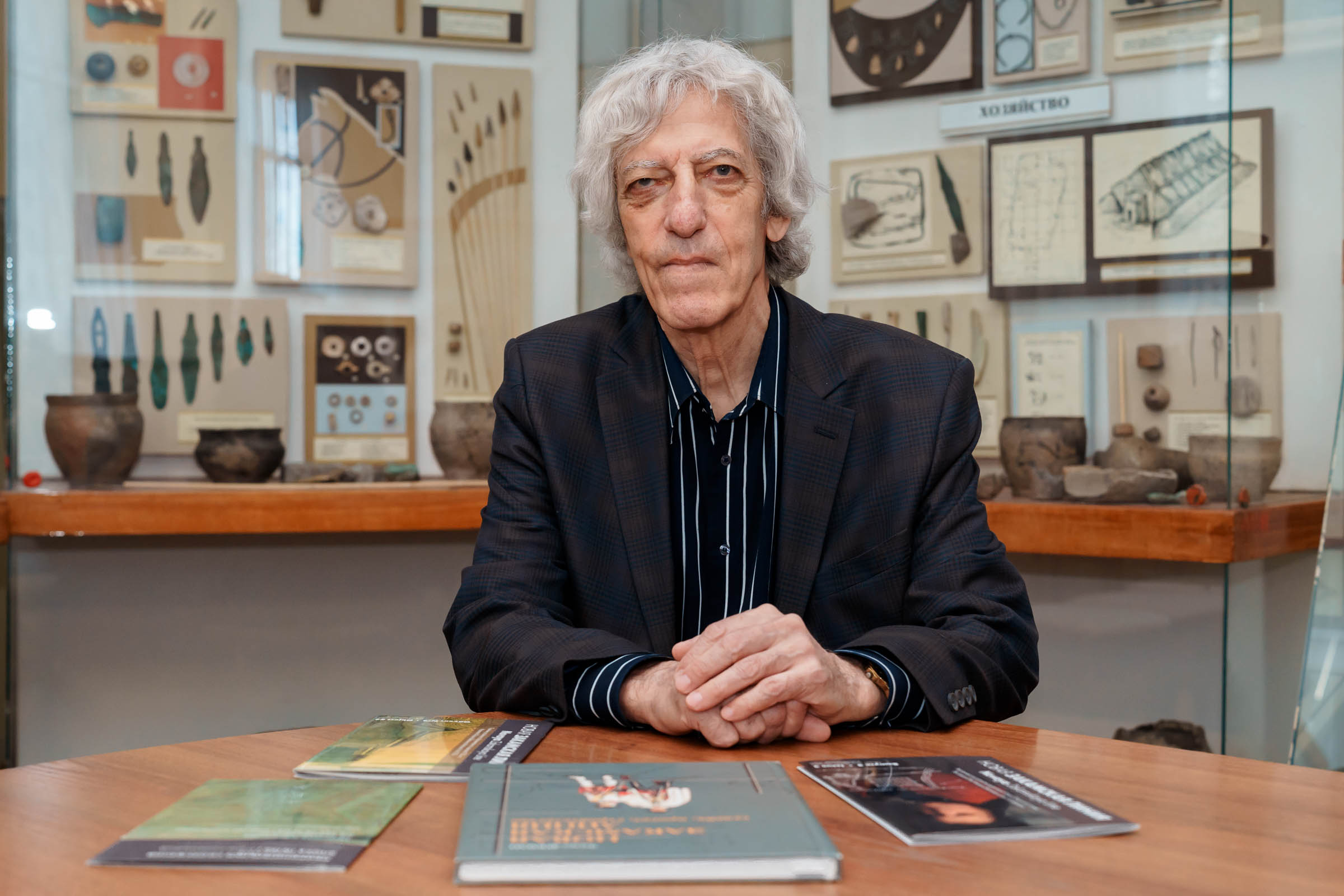

The authors of this guidebook, published in the form of three colorfully illustrated booklets in Russian and English, were Eduard Dubman, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor of the Department of Russian History at Samara National Research University, and Tatiana Vavilonskaya, Doctor of Architecture, Professor, Head of the Department of Reconstruction and Restoration of Architectural Heritage of the Academy of Construction and Architecture of Samara State Technical University. The popular science publication was prepared on the initiative and with the support of the State Inspectorate for the Protection of Cultural Heritage Sites of the Samara Region and is intended for anyone who likes to travel around Russia and is interested in its history.

"The New Zakamskaya Line is a unique monument of Russian fortification architecture. The defensive line with a total length of 260 km passes through the territories of seven districts of the Samara region and two districts of Tatarstan and is one of the few well-preserved examples of late frontier fortification in Russia in the first half of the 18th century. This is, of course, an outstanding example of the engineering thought of Russian military engineers who creatively developed the Western European experience of constructing such fortifications using earth as the main building material," said Eduard Dubman.

According to the scientist, active development and settlement of territories in the south and south-east of the future Russian Empire has been going on since the end of the 15th–17th centuries. However, intensive development of the southern forest-steppe of the Samara Trans-Volga region began only in the 18th century. This was due to the fact that Russians were simply afraid to settle on the lands of the Left Bank of the Volga River due to the constant attacks of nomads. Local military leaders wrote to Moscow that it was dangerous to settle people across the Volga River "due to arrival of military men".

It can be argued that the beginning of the active settlement of the Samara Trans-Volga region was largely due to Peter the Great's special interest in the natural resources of these places. In the first printed issue of the first Russian newspaper Vedomosti, published in January 1703, the news was published that "a lot of oil and copper ore were found on the Sok River, and a lot of copper was smelted from that ore, which could be a considerable profit to the Moscow state." As you know, Russia waged a difficult war with Sweden at the beginning of the 18th century. At first, there was not enough metal to cast cannons, and there was especially a shortage of gunpowder. For the manufacture of gunpowder, sulfur was needed, deposits of which were also discovered in the area of the Sok River.

At first, a chain of redoubts, or so-called "Cheremshan outposts," was created in the Trans-Volga region to protect local residents and sulfur "factories" from raids by steppe nomads, to which large military forces from Kazan and its suburbs advanced every spring. But this was not enough, and in the early 1730s, the government of Empress Anna Ioannovna decided to erect a large-scale continuous fortified line. Its construction began in 1731. By the way, Major General Andrey de Brilly was initially appointed as the head of this project, but after a couple of months he lost this position for some reason. (It is assumed that he could be the prototype of the very Chevalier de Brilly, brilliantly played by Mikhail Boyarsky in the film "Midshipmen, go!" However, the real de Brilly was a military engineer and an Italian, and not a schemer and a Frenchman, as in the film).

The construction of the line has been underway since the autumn of 1731 for more than four years and was forced to end in the autumn of 1735, that is, in 2025, the New Zakamskaya Line will be 290 years old. The annual construction work in 1732–1735 was carried out in two shifts, starting in late spring and covering the first months of autumn. Up to 10,000 or more people were supposed to be mobilized in each shift, but much fewer were going to the construction site. In total, two fortresses were built — Krasnoyarsk and Cheremshanskaya, in addition, two suburbs, Alekseevsk and Sergievsk, founded in the mid-1710s, were rebuilt and fortified, and four fieldworks (fortresses of reduced size), ten redoubts and one retrenchment (internal defensive fence) were built.

Earthen ramparts up to 2.5–3 meters high and ditches up to 2–2.5 meters deep, stretching across the entire open steppe space from the Kinelsky redoubt to the suburbs of Sergievsk, combined the defensive system into a single whole. The earthworks of fortresses and fieldworks were much more powerful. To the north of the Sok River, beyond Sergievsk, forests began, along the outskirts of which zasekis — fortifications from felled and specially laid tree trunks — were created. A mandatory element of the line were wooden watchtowers called "lighthouses". If nomads appeared, fires were lit at the lighthouses to raise the alarm. This defense system was defended by four regiments of the land militia settled in the Trans-Volga region, for which settlements were built along the line under the protection of earthen fortifications.

"The structures of the New Zakamskaya Line are mainly earthen fortifications and to a lesser extent are made of trees. During the construction of the line, Russian engineers achieved the adaptation of unique samples of defensive construction technologies used in the 18th century to the local Russian natural conditions. Almost three centuries have passed since the construction, and the earthen structures, although they have lost significant wooden details, still retain their clear geometric shape, and they are perfectly visible to the naked eye. The spectacular nature of these defensive structures often attracted the attention of researchers. For example, they were examined and described by Vasily Tatishchev, the author of The History of Russia, the first major work on Russian history, as well as the founder of Stavropol-on-the-Volga, now Togliatti," said Eduard Dubman.

If we take the modern cartography of the Samara region, then the New Zakamskaya Line runs from south to east from Samara along the river of the same name through Alekseevka in the Kinelsky district, and then turns sharply north at the mouth of the Bolshoy Kinel, crosses the watershed and goes to the Sok River, at the confluence of the Kondurchi River and further from the Krasnoyarsk Fortress, based on the totality moats and ramparts, as well as one fieldwork and several redoubts, reaches Sergievsk. Then it turns to the northeast and, crossing the forests of the Isaklinsky, Shentalinsky and Chelno-Vershinsky districts, goes beyond the Cheremshan River and the fortress of the same name into the territory of modern Tatarstan. Further, passing through the territories of Cheremshansky and Almetyevsky districts, the line ends at the Kichui River.

The pages of the booklets are decorated with fragments of ancient maps and photographs of defensive structures in various locations, including colorful bird’s-eye views of the line, the history of fortifications is described in detail, and the internal structure of fortifications is shown in the form of diagrams and drawings. According to Eduard Dubman, this publication, along with the monograph "The New Zakamsky Line: Fate, Project, Construction" published two decades earlier, can help develop historical and cultural tourism in the region and interest people who are not indifferent to Russian history, who may want to personally see this unique historical monument and literally the sense of touching history.

"Undoubtedly, the New Zakamsky Line has a special significance for the history of Russia and world history in general. Currently, work is continuing on the study and museumification of cultural heritage sites of the fortification system. Archaeological research is also continuing," said Eduard Dubman.

Photo by: Olesya Orina

RU

RU  EN

EN  CN

CN  ES

ES